Seven (7). That is how many copies of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone live in my house. I mention this because if you’ve read Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, you may recall that seven is a powerfully magical number. Do with this information what you will.

Now then, how does one end up with seven copies of Harry Potter number one? Let’s do the tally:

Two hardcover U.S. editions +

one paperback U.S. edition +

two paperback U.K. editions +

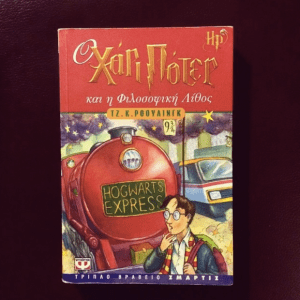

one Greek translation (in paperback) +

the e-book edition =

Seven editions of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s/Philosopher’s Stone. In my house.

My Harry Potter journey didn’t begin until 2004, with one copy of the Greek translation and one copy of the British paperback edition. You see, when Harry Potter was first released, I was well out of the target demographic so missed it entirely. By the time it became big enough for even me, technically a grown-up, to notice, I was in one of my phases (Russian classics, if I’m not mistaken) and thus couldn’t be bothered with a “children’s book” (in quotes because I was in graduate school at the time, and we academics seem to enjoy putting quotes around words for no earthly reason).

My turning point came when I was searching for a book to read in Greek. Reading is one way I attempt to maintain my Greek language skills. Since I have the vocab of a fourth grader (I’m being generous – it’s probably more like a first grader’s), reading literary fiction is, to put it mildly, slow going indeed. And never you mind that Greek is phonetic.

This is why I favor reading children’s books that I can also find in English. Reading a book for young readers means I’m not looking up every other word (literally), which means I can often derive the meaning in context, which means I’m more likely to remember it. Where the English editions come in is that I’ll read one chapter in Greek then the same one in English to get the larger gist, which then also helps me remember more new words. I’m probably making it sound more complicated than it is.

Anyway, this was how I decided on Harry Potter. Being a children’s book easy to find in both languages, it met a particular need at a particular time. As I was in Greece for the momentous occasion, I purchased the Greek translation and paperback U.K. edition at Eleftheroudakis Bookstore in Athens and commenced reading the novel, alternating my chapters from Greek to English, like I do.

And then around chapter four (The Keeper of the Keys), a funny thing happened. It seems I forgot to continue alternating chapters and carried on reading the English edition straight through to the end. You see, I was having such fun reading the story that my homework fell by the wayside (shades of secondary school all over again). I did return to the Greek edition … eventually … after I’d finished the English edition.

Even if you’ve never read the novel, you probably know the story: Orphaned boy raised by cruel relations discovers the secret of his parentage and his own prodigious magical gifts. He acquires wizard trappings including wand, cauldron, robes and goes to boarding school where he studies spells, potions, and charms and rides a broomstick. Pumpkin-related edibles on hand include pumpkin pasties and pumpkin juice.

Here’s what I haven’t admitted yet: When I first heard of the novel, I thought I sounded kind of corny. I like pumpkin-spice lattes as much as the next New Englander, but it all seemed a bit … cliché. Wands, pointed hats (that sing, no less), cauldrons for brewing potions, riding broomsticks … I dunno about this.

Upon actually reading the whole novel, instead of just having an opinion of it, I was reminded of something I shouldn’t ever have forgotten, even momentarily: There are no new stories only new ways of telling them. And that is what J. K. Rowling did so exceedingly well: She took the cultural trappings of the witch world, so pervasive that we might be tempted to call them cliché, and transformed (you might even say transfigured, wink, nudge) them into a funny, engaging, well-crafted story with a serious message about the power of choice, love, and community.

Reading Harry Potter shows me how parody (of the world of witches as they’re portrayed in popular culture) can become a way to show us how the capacity for finding meaning always lurks underneath what we may be tempted to dismiss, for whatever reason(s). Incidentally, if you want to read another English novel that does just this, check out Jane Austen’s “Northanger Abbey,” in which she parodies gothic novels while also championing the novel as a serious art form.

Rowling writes within the larger tradition of English literature in other ways as well, for example abused orphans, boarding school, and redemption as portrayed in Charlotte Brontë and Charles Dickens. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg, as it were. In addition to three authors already mentioned, I can see traces of Enid Blyton, Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, and Emily Brontë.

Which brings up back to the powerfully magical number seven.